Below these remarks lies one of the more depressing articles in market history.

We see that the SEC has something called an "office of economic analysis". One wonders what they analyze. One only had to call any slightly sophisticated (on that note, I wrote about this on September 17, 2007) market participant and ask them what the ramifications would be.

And notice the tone..."it could have been much worse...we could have ignored everything and declared the equivalent of Martial Law on the markets and shut them down, so we should be thankful". Ah yes, what a master minister Mr. Cox is turning out to be.

Beyond that, the Treasury and Fed should be asked why they created "intense pressure" for the SEC to enact the short-selling rule. Who put pressure on the SEC to temporarily re-write existing rules...and for whose benefit?

By Rachelle Younglai

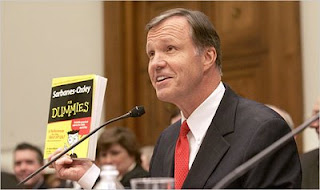

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - Under fire for regulatory missteps, top U.S. securities regulator Christopher Cox defended his agency's record but acknowledged some regrets over how he handled the worst financial crisis in decades.

The Securities and Exchange Commission has been lambasted by lawmakers and others for not doing enough to prevent the 2008 collapse of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers, interfering with markets and failing to detect the alleged $50 billion fraud at Wall Street financier Bernard Madoff's firm.

Cox, a Republican and former California congressman, said the SEC's focus has been customer protection and broker dealer regulation and that the agency "performed that traditional role superbly."

However, Cox said he had some regrets over a drastic action the agency took as markets were hurtling downward in September. For a few weeks, the SEC stopped investors from making bearish bets on financial stocks like Morgan Stanley (MS.N) and Citigroup (C.N).

The SEC's office of economic analysis is still evaluating data from the temporary ban on short-selling. Preliminary findings point to several unintended market consequences and side effects caused by the ban, he said.

"While the actual effects of this temporary action will not be fully understood for many more months, if not years, knowing what we know now, I believe on balance the commission would not do it again," Cox told Reuters in a telephone interview from the SEC's Los Angeles office late on Tuesday. "The costs appear to outweigh the benefits."

Less liquidity in the markets was one of the unintended consequences, experts have said.

The SEC imposed the temporary ban under intense pressure from the Federal Reserve and Treasury Department which insisted it was crucial to the short-term survival of these institutions, Cox said.

A few weeks after the temporary ban was lifted, global markets were again dropping precipitously, U.S. banks were begging the SEC to reinstate its short-sale ban and there was talk of shutting the markets down.

Cox said the chief executive of one major U.S. investment bank even urged suspension of normal trading rules across the entire U.S. market, likening the situation to how Abraham Lincoln suspended habeas corpus during the Civil War and Franklin Roosevelt sent Japanese-Americans to internment camps during World War Two.

The chief executive said, "that is how America made it through such crises, and we couldn't be too focused on maintaining the rule of law," Cox said. "That was advice we rejected."

Cox said he spoke to the White House, the chief executives the New York Stock Exchange and the Nasdaq, strongly urging them to keep the U.S. markets open.

Markets were never shut down and Wall Street investment banks weathered the market turmoil largely by transforming themselves into commercial banks.

It has been a rough year for Cox, who was recruited by the George W. Bush administration in 2005 to heal a fractious agency.

Initially, Cox managed to propose and adopt rules with little dissent from the agency's four other commissioners. He focused on modernizing the SEC, set a timetable for companies to submit financial reports with XBRL or interactive data, and reached agreements with the SEC's foreign counterparts to improve international enforcement.

Under Cox's watch, the agency also brought the second-highest number of enforcement actions in 2008 since a record in 2003 when staff dealt with fallout from the high-profile implosion of Enron.

However, his tenure as SEC chief will be colored by his handling of Wall Street's meltdown.

Cox said he tries to keep the criticism in perspective.

"If you know that you are doing everything you can to improve conditions for investors and markets ... if you know that the team of professionals that is working on the mission is first-rate, that is ample comfort against what are sometimes hastily drawn conclusions by others."

No comments:

Post a Comment